Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)

An axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is surgery to remove lymph nodes from the armpit (underarm or axilla). The lymph nodes in the armpit are called axillary lymph nodes. An ALND is also called axillary dissection, axillary node dissection or axillary lymphadenectomy.

The lymph nodes are part of the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system helps fight infections and is made up of lymph vessels, lymph fluid, lymph nodes, bone marrow and the lymphatic organs (thymus, adenoid, tonsil and spleen).

Lymph vessels are very thin tubes similar to blood vessels. They collect and move lymph fluid away from tissues into the lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped organs of lymphatic tissue. The lymph fluid can carry cancer cells from where the cancer started into the lymph nodes.

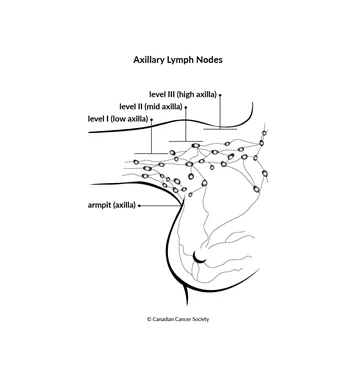

The axillary lymph nodes are divided into 3 levels:

- level I (low axilla) – located in the lower part of the armpit

- level II (mid axilla) – located in the middle part of the armpit

- level III (high axilla) – located in the upper part of the armpit near the breastbone (sternum)

Cancer cells usually spread to the level I lymph nodes first, to level II next and then to level III.

Lymph fluid from the breast, skin of the upper limbs and other nearby tissues drains into the axillary lymph nodes. The lymph fluid can carry cancer cells from these areas into the axillary lymph nodes. In the early stages, you cannot usually feel the cancer in the axillary lymph nodes. In more advanced stages of cancer, you may feel a lump in the armpit as the axillary lymph nodes get bigger.

The most common type of cancer that spreads to the axillary lymph nodes is breast cancer. Other cancers that may spread to the axillary lymph nodes are skin cancers, such as melanoma or non-melanoma. Some types of cancer start in the axillary lymph nodes.

Why an axillary lymph node dissection is done

An axillary lymph node dissection is done to:

- check for cancer in the lymph nodes of the armpit

- find out how many lymph nodes contain cancer and how much cancer has spread to them

- remove lymph nodes that contain cancer

- remove lymph nodes when there is a high chance that cancer will spread to them

- reduce the chance that the cancer will come back (recur)

- remove cancer that is still in the lymph nodes after radiation therapy or chemotherapy

- help doctors plan further treatment

How an axillary lymph node dissection is done

An ALND is done under general

The surgeon makes a cut (incision) under the arm and removes 10–40 lymph nodes from level I and level II. Level III lymph nodes are not usually removed because this does not improve survival and it increases the chances of side effects. But level III lymph nodes may be removed if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes and formed a lump in the armpit or if bigger nodes are seen on imaging tests (such as an ultrasound, a CT scan or an MRI).

The lymph nodes and any other tissue removed during surgery are sent to a lab to be examined by a doctor who specializes in the causes and nature of disease (a pathologist).

After removing the lymph nodes, the surgeon places a small tube (drain) and closes the cut with stitches or staples. A drainage bag is attached to the end of the tube to collect fluid draining from the area. This reduces the chance of fluid building up and improves healing. The drain is left in place for a few weeks or until there is little drainage.

People who have an ALND are usually sent home 1–2 days after surgery. You may be given:

- antibiotics to prevent infection

- pain-relieving medicine

- instructions on caring for and dressing the wound

- information about how to manage the drainage bag and tube

- advice on how much and which types of activity you can do after surgery

- instructions on what to wear

- advice on the best positions for your arm

- a follow-up appointment to see the surgeon in 1–2 weeks

- information about which symptoms and side effects you should report

Side effects

Side effects can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after an ALND. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after an ALND. Most side effects go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Tell the healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think may be from an ALND:

- signs of infection, such as pain, redness, pus, discharge or fever

- a collection of fluid under the skin (seroma) in the armpit near the cut

- a swollen and tight-feeling arm

- stiffness or trouble moving the arm or shoulder

- changes in sensation, such as pain or numbness (may happen if nerves are damaged)

- chronic pain (may be caused by damage to the nerves in the armpit)

- axillary web syndrome (AWS, also called lymphatic cording), which is when cords of scar tissue develop in the lymph vessels from the armpit to the elbow and causes pain, tightness in the arm and trouble moving the shoulder

The healthcare team may give you antibiotics to prevent or treat an infection, or they may drain a buildup of fluid.

Swelling may be due to a buildup of lymph fluid in the soft tissues (called lymphedema) . Lymphedema can happen any time after lymph nodes are removed, but it is more common with an ALND. The chance of developing lymphedema increases with the number of lymph nodes removed and if radiation is given after an ALND. About 1 in 5 people get mild lymphedema after an ALND. A small percentage of people may get severe lymphedema. Lymphedema treatment may include massage therapy, compression garments and exercises.

What the results mean

Each lymph node removed is examined to see if it contains cancer.

- A negative lymph node has no cancer cells.

- A positive lymph node has cancer cells.

The pathologist’s report includes the type of cancer, the number of lymph nodes removed and the number of lymph nodes that have cancer cells. The report may also say if the cancer has grown through the outer covering of the lymph node (the capsule).

Doctors use the number of positive lymph nodes to help

Depending on the result, your doctor will decide if you need more tests, any treatment or follow-up care.

Special considerations for children

In rare cases, an ALND may be done in children to stage or treat some cancers, such as childhood breast cancer or rhabdomyosarcoma.

Preparing children before a test or procedure can lower anxiety, increase cooperation and help them develop coping skills. Preparation includes explaining to children what will happen during the test, including what they will see, feel, hear, taste or smell.

Preparing a child for an ALND depends on the age and experience of the child. Find out more about helping your child cope with tests and treatments.