Bladder problems

Bladder problems can develop after some types of cancer treatment. Sometimes bladder problems happen as a late effect of treatments for cancer during childhood.

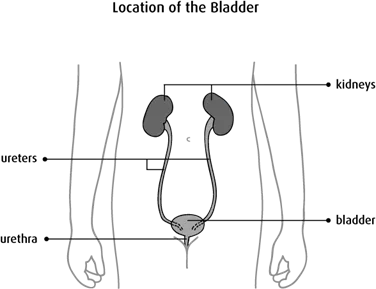

How the bladder works

The bladder is part of the urinary system. It is a hollow organ in the lower abdomen, behind the pubic bone. The bladder has a flexible, muscular wall that allows it to get larger. The kidneys filter the blood and make urine, which enters the bladder through 2 tubes called ureters. The bladder stores urine, and then it passes out of the body through another tube called the urethra.

Causes

Treatments for cancer, including some types of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and surgery, can cause bladder problems.

Chemotherapy

Some chemotherapy drugs break down into substances that irritate the lining of the bladder when they are passed in the urine. The irritation can cause inflammation and bleeding. In rare cases, it can become severe and lead to permanent damage.

Chemotherapy drugs that most commonly cause bladder irritation are:

- cyclophosphamide (Procytox)

- ifosfamide (Ifex)

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy to the bladder or pelvis can cause damage to the bladder.

Surgery

Types of surgery that can cause bladder problems include:

- surgery to remove all or part of the bladder

- surgery to the pelvis such as the removal of the prostate in men or the uterus in women

- surgery to the central nervous system

Other causes

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and other drugs that are given through a tube directly into the bladder can also cause irritation.

Types of bladder problems

Bladder problems that can develop after treatment for cancer include:

- bleeding caused by inflammation of the bladder wall (called hemorrhagic cystitis)

- scar tissue (fibrosis) buildup or nerve damage (called neurogenic bladder), which can lead to incontinence and trouble storing urine or emptying the bladder

- smaller bladder size

- blockage in the kidney, bladder, ureter or urethra

- urinary tract infections

Problems that affect the bladder’s ability to store and empty urine can lead to kidney damage over time.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms that may suggest bladder damage include:

- blood in the urine

- burning or pain when urinating

- an intense need to urinate

- a need to urinate often

- feeling that the bladder has not emptied completely

- feeling the need to urinate without being able to do so

- difficulty emptying the bladder

- incontinence, which is little or no bladder control

- pain above the pubic bone

- bladder spasms

- fever or chills

If symptoms get worse or don’t go away, report them to your doctor or healthcare team without waiting for your next scheduled appointment.

Diagnosis

Before treatment for cancer begins, the healthcare team may do tests to check the bladder and make sure there are no major problems. Tests may also be done during and after treatments to make sure nothing has changed.

Bladder problems are usually diagnosed by:

- a physical exam

- a urinalysis

- blood chemistry tests

- an ultrasound of the bladder

- an intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

- a cystoscopy

Find out more about these tests and procedures.

Preventing bladder problems

To prevent bladder problems, the healthcare team carefully monitors people who are at risk. They use tests, including urinalysis and blood chemistry tests, to monitor and check the bladder in people receiving cancer treatments that can affect the bladder.

- The bladder is shielded during radiation therapy, if possible, to prevent damage.

- To help protect the bladder from irritation during chemotherapy, the healthcare team may give extra fluids by a needle in a vein (intravenously). The drug mesna (Uromitexan) is usually given before, during or after chemotherapy that may damage the bladder.

You can also help lower your risk for bladder problems by:

- drinking extra fluids before receiving chemotherapy and for at least 24 hours after treatment

- emptying your bladder often, including during the night

- avoiding tea, coffee, pop and other caffeinated drinks

- avoiding spicy foods and alcohol

Managing bladder problems

If bladder problems develop from cancer treatment, your healthcare team will make a plan to help manage the symptoms.

- Medicines may be given to control any bladder spasms.

- For severe bleeding, the healthcare team may flush the bladder (bladder irrigation), give you medicines to treat inflammation and stop the bleeding, or stop chemotherapy treatment.

- Bladder fibrosis and smaller bladder size may be managed with exercises to increase how much urine the bladder can hold. Sometimes surgery is done to make the bladder larger.

- Some people with neurogenic bladder can’t completely empty the bladder or can’t urinate at all. Neurogenic bladder may be treated with medicine or surgery. It may also be managed by placing a tube (catheter) into the bladder at certain times to drain urine (called intermittent catheterization). The healthcare team will explain how to do this.

Follow-up

All people who are treated for cancer need regular follow-up. The healthcare team will develop a follow-up plan based on the type of cancer, how it was treated and your needs.

Make sure you tell your doctor all the treatments you received. If you are at risk for bladder problems, you should have a physical exam each year. The doctor will ask questions about your bladder.

Tests may include:

- a urinalysis

- blood tests

- an ultrasound of the bladder