Surgery for pancreatic cancer

Surgery is usually used to treat pancreatic cancer. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the size and location of the tumour, whether the cancer has spread and if the doctor thinks the tumour can be completely removed.

Surgery may be done for different reasons. You may have surgery to:

- try to completely remove the tumour

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

Even with the advanced tests that doctors use to diagnose pancreatic cancer, they can’t always tell the stage of the cancer until they do surgery. Based on imaging tests, they may think that a tumour can be removed with surgery (is resectable). But they may find out during surgery that the tumour can’t be removed (is unresectable) or that the cancer has spread (metastasized).

If doctors find that the tumour is unresectable or that the cancer has spread, they may do palliative surgery. This type of surgery is used to relieve pain or to treat or prevent symptoms caused by a blockage in the common bile duct or duodenum (first part of the small intestine).

Surgery for pancreatic cancer is done by surgeons who are specialized in pancreatic cancers (called hepatopancreaticobiliary or HPB surgeons). Surgery is done at centres with experience in doing these surgeries. The following types of surgery are used to treat pancreatic cancer or relieve symptoms of advanced cancer. You may also have other treatments before or after surgery.

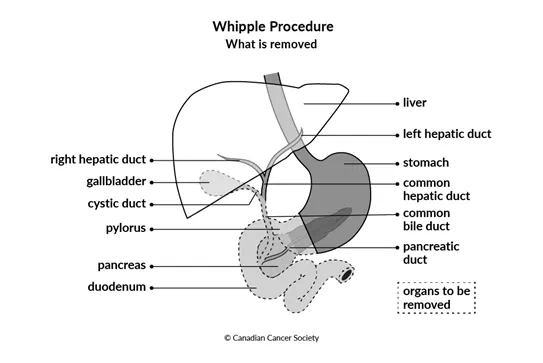

Whipple procedure

The Whipple procedure (also called pancreaticoduodenectomy) is the most common surgery for pancreatic cancer. It is used to remove tumours in the head of the pancreas or in the opening of the pancreatic duct. This surgery removes:

- the head of the pancreas along with the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine)

- the gallbladder

- part of the common bile duct

- the pylorus (bottom part of the stomach that attaches to the duodenum)

- lymph nodes near the head of the pancreas

After removing these organs, the surgeon attaches the remaining end of the stomach to the jejunum (called gastrojejunostomy). The rest of the common bile duct and pancreas are also attached to the jejunum so bile and pancreatic juices can flow into the jejunum. These juices help to neutralize stomach acid and lower the risk of an ulcer in the area.

Find out more about the Whipple procedure.

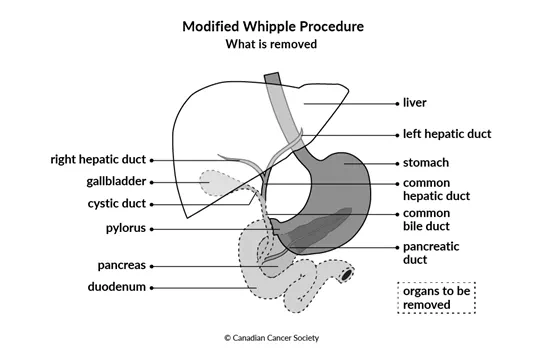

Modified Whipple procedure

The modified Whipple procedure (also called pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy) removes all of the same organs as the Whipple procedure except for the pylorus.

After removing these organs, the surgeon attaches the part of the remaining duodenum that is attached to the stomach to the jejunum (called duodenojejunostomy). The rest of the common bile duct and pancreas are also attached to the jejunum so bile and pancreatic juices can flow into the jejunum.

This surgery doesn’t remove any of the stomach, so it can still work normally. People who have the modified Whipple procedure don’t have the nutrition problems that can develop after the Whipple procedure.

Surgeons can only use the modified Whipple procedure if:

- it isn’t a large, or bulky, tumour in the head of the pancreas

- the tumour hasn’t grown into the first part of the duodenum

- there are no cancer cells in the lymph nodes around the pylorus (called the pyloric and peripyloric lymph nodes)

Find out more about the modified Whipple procedure.

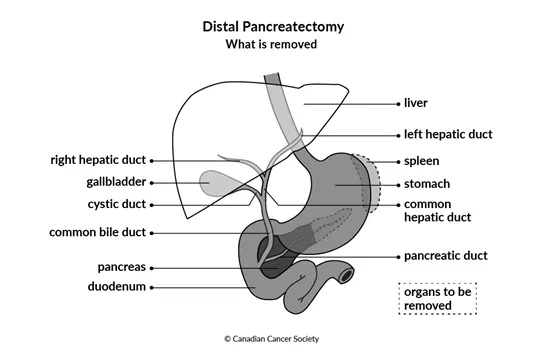

Distal pancreatectomy

A distal pancreatectomy may be done for a tumour in the body or tail of the pancreas. This surgery removes the tail of the pancreas, or the tail and part of the body of the pancreas, and nearby lymph nodes. The spleen is only removed if the tumour has grown into the spleen or blood vessels supplying the spleen. The head of the pancreas remains joined to the duodenum.

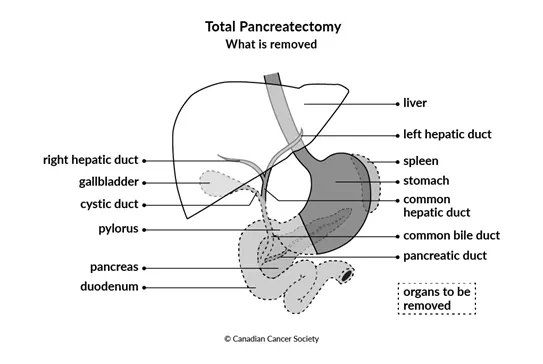

Total pancreatectomy

A total pancreatectomy is rarely done. Doctors may consider using this surgery if cancer has spread through the entire pancreas, if cancer is found in many areas of the pancreas or if the pancreas can’t be safely connected to the small intestine.

This surgery removes all of the pancreas, the duodenum, the pylorus, part of the common bile duct, the gallbladder, sometimes the spleen and nearby lymph nodes.

After removing these organs, the surgeon attaches the remaining end of the stomach to the jejunum (called gastrojejunostomy). The rest of the common bile duct is also attached to the jejunum so bile can flow into the jejunum.

Because the entire pancreas is removed, people who have this surgery will have diabetes and will need to take insulin. The diabetes is often difficult to control.

The pancreas normally makes enzymes that help you digest food. People who have a total pancreatectomy will have to take enzyme replacements for the rest of their lives.

Palliative surgery

Palliative surgery may be used to relieve symptoms of unresectable (locally advanced or metastatic) or recurrent pancreatic cancer.

Tumours in the head of the pancreas often block the common bile duct or the duodenum. Palliative surgery may be done to relieve symptoms of a blockage.

Stent placement

Stent placement is the most common way to relieve a blockage caused by a pancreatic tumour. A stent is a thin, hollow tube that is usually made of metal. It is placed into a bile duct and keeps it open by putting pressure on the walls of the duct from the inside. With a stent in place, bile can drain into the small intestine as it normally would.

A stent is usually placed into the bile duct during an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). This is called endoscopic stent placement. In some cases, doctors will make a cut (incision) through the skin to place the stent in the bile duct (called percutaneous method). When this is done, the bile drains into a bag outside the body.

A stent can get blocked after it is in place. The stent may need to be replaced every 3 to 4 months, or even more often. Newer types of stents are wider and expandable. They are being used to help keep the bile duct open longer.

Surgical bypass

In general, endoscopic stent placement has replaced surgical bypass procedures. But in some cases, a surgical bypass may still be done to relieve a blockage caused by a pancreatic tumour. For example, if surgery to remove the tumour is attempted but the tumour is found to be unresectable, a surgical bypass may be done.

The type of surgical bypass used to help bile flow around a blockage is called a biliary bypass. Different biliary bypass operations are used depending on the location of the blockage.

Choledochojejunostomy joins the common bile duct to the jejunum (the middle part of the small intestine).

Hepaticojejunostomy joins the common hepatic duct to the jejunum. The common hepatic duct carries bile from the liver.

Gastric bypass, or gastrojejunostomy, joins the stomach directly to the jejunum. This surgery is sometimes used to avoid a second surgery if it is likely that the duodenum will become blocked as the disease progresses.

Side effects

Side effects can happen with any type of treatment for pancreatic cancer, but everyone’s experience is different. Some people have many side effects. Other people have only a few side effects.

If you develop side effects, they can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery and your overall health.

Surgery for pancreatic cancer may cause these side effects:

- pain

- infection

- bleeding

- leaking of bile, stomach acid or pancreatic juices from where the healthy ends of the stomach, the duodenum or a bile duct were joined during surgery

- delayed gastric emptying (when food stays in the stomach longer than usual) causing nausea, vomiting and a full feeling

- dumping syndrome( when food moves too fast from the stomach into the small intestine)

- nutrition problems, such as poor appetite, poor fat absorption, diarrhea, bloating and indigestion

- diabetes

Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Questions to ask about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.