Types of multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma is the most common type of plasma cell cancer. The bones and bone marrow are the main sites where myeloma cells (abnormal plasma cells) are produced. The myeloma cells can form tumours, called plasmacytomas, in many bones in the body.

The buildup of myeloma cells causes:

- fewer normal blood cells in the bone marrow

- weakened or damaged (fractured) bones

- bone pain

- infection

When the bones are weakened or damaged, 2 types of bone cells don’t work together the way they usually do. Osteoblasts make bone and osteoclasts break down bone. Myeloma cells stimulate the osteoclasts to break down bone at a much quicker rate than normal.

There are 2 main types of multiple myeloma, smouldering and active. Smouldering multiple myeloma doesn’t have signs and symptoms of the disease. Active multiple myeloma has signs and symptoms.

Smouldering (indolent) multiple myeloma

Smouldering (indolent) multiple myeloma is also called asymptomatic myeloma because it does not cause any symptoms. This type of myeloma is a condition between monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance( MGUS, a precancerous condition) and active (symptomatic) multiple myeloma. People with smouldering multiple myeloma have at least one of the following features:

- Plasma cells make up 10% or more of the blood cells in the bone marrow.

-

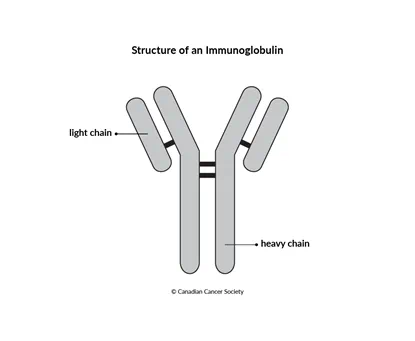

The M-protein level in the blood is 30 g/L or more. An M-protein is one

type of

immunoglobulin that is made by abnormal plasma cells.

Most people with smouldering multiple myeloma will eventually develop multiple myeloma with symptoms (active multiple myeloma).

People with smouldering multiple myeloma go for regular tests every 3–6 months to see if their condition is progressing to active multiple myeloma. Only those people with very high risk smouldering multiple myeloma may get treatment for multiple myeloma.

Learn more about tests for multiple myeloma.

Risk groups

Doctors try to predict when people with smouldering multiple myeloma will develop active multiple myeloma.

Low-risk smouldering multiple myeloma

You have low-risk smouldering multiple myeloma if you have both of these features:

- Plasma cells make up less than 10% of the blood cells in the bone marrow.

- The M-protein level in the blood is 30 g/L or more.

On average, people with low-risk smouldering multiple myeloma progress to active multiple myeloma about 19 years after their diagnosis.

Intermediate-risk smouldering multiple myeloma

You have intermediate-risk smouldering multiple myeloma if you have both of these features:

- Plasma cells make up 10% or more of the blood cells in the bone marrow.

- The M-protein level in the blood is less than 30 g/L.

On average, people with intermediate-risk smouldering multiple myeloma progress to active multiple myeloma about 9 years after their diagnosis.

High-risk smouldering multiple myeloma

You have high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma if you have both of these features:

- Plasma cells make up 10% or more of the blood cells in the bone marrow.

- The M-protein level in the blood is 30 g/L or more.

On average, people with high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma progress to active multiple myeloma about 2 and a half years after their diagnosis.

Some people with high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma have a very high risk of progressing to active multiple myeloma within 2 years after their diagnosis if they have all of these features:

- Plasma cells make up 60% or more of the blood cells in the bone marrow.

- The serum free light chain ratio is 100 or greater.

- An MRI scan shows more than one area of bone or bone marrow destruction (breakdown).

If you have this type of high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma, you will be treated as if you have stage 1 multiple myeloma.

Active (symptomatic) multiple myeloma

People with multiple myeloma who have symptoms related to the disease and any of the following features have active (symptomatic) multiple myeloma.

- M-protein in the blood or urine

- plasma cells that make up 10% or more of the blood cells in the bone marrow

- a tumour that contains myeloma cells (called a plasmacytoma) in the bone or soft tissue

- anemia, kidney failure or high blood calcium (hypercalcemia)

- osteolytic lesions (weakened areas of bone seen on an x-ray)

Solitary plasmacytoma of the bone

A plasmacytoma develops when abnormal plasma cells collect in one place and form a single tumour. Solitary plasmacytoma of the bone is a single tumour made up of myeloma cells found in one bone (rather than multiple tumours, or more than one tumour, in different locations, as in multiple myeloma). There are no other features of multiple myeloma. X-rays of the bones show only one osteolytic lesion at the location of the plasmacytoma. Plasma cells make up less than 10% of all of the cells in the bone marrow. The main symptom of a solitary plasmacytoma of the bone is pain at the site of the tumour. A solitary plasmacytoma is most often treated with radiation therapy.

About one-third of people with solitary plasmacytoma will eventually develop other plasmacytomas and multiple myeloma.

Extramedullary plasmacytoma

Extramedullary plasmacytomas start outside the bone marrow (extramedullary) in soft tissues of the body. It is most common in areas of the upper respiratory tract, such as the throat, sinuses around the nose (called paranasal sinuses), nasal cavity and larynx (voice box). It may also occur in other areas, including the gastrointestinal tract, breast and brain. A diagnosis of extramedullary plasmacytoma is made after a biopsy of the tumour. People with extramedullary plasmacytoma have normal x-rays and bone marrow biopsies. They may have an MRI or a PET scan to check other areas of the body that may show signs of cancer.

The main treatment for extramedullary plasmacytoma is radiation therapy, surgery or both.

Light chain myeloma

Some people with multiple myeloma have myeloma cells that don’t make a complete immunoglobulin. People with light chain myeloma only make the light chain part of the immunoglobulin and not the heavy chain.

Light chains can collect in and damage the kidneys. Light chains are smaller than M-proteins and show up better in the urine than the blood. This is because light chains are filtered out of the blood when they reach the kidneys. Light chains in urine are also called Bence-Jones proteins. About 15%–20% of people with multiple myeloma have light chain myeloma.

Non-secretory myeloma

Some people with multiple myeloma have myeloma cells that do not release (secrete) enough M-proteins or light chains into the blood or urine to be detected by protein electrophoresis. In non-secretory myeloma there are myeloma cells in the bone marrow. X-rays will also show osteolytic lesions in a person with non-secretory myeloma.

Rare types of multiple myeloma

The most common immunoglobulins (Ig) made by myeloma cells in multiple myeloma are IgG and IgA. The least common are IgD and IgE.

Immunoglobulin D (IgD) myeloma

About 2% of people with multiple myeloma have the IgD type. IgD multiple myeloma causes the same signs and symptoms as other types of multiple myeloma. IgD myeloma tends to affect people at a slightly younger age (around 54 years old on average).

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) myeloma

IgE is the rarest type of multiple myeloma. IgE multiple myeloma causes the same signs and symptoms as other types of multiple myeloma. It tends to be aggressive and progresses to plasma cell leukemia or spreads outside the bone marrow quickly.