Surgery for anal cancer

Surgery is a medical procedure to examine, remove or repair tissue. Surgery, as a treatment for cancer, means removing the tumour or cancerous tissue from your body.

Surgery is sometimes used to treat anal cancer. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the size of the tumour, the stage of the cancer and your response to other treatments you have had for anal cancer.

Surgery may be the only treatment you have or it may be used along with other cancer treatments. You may have surgery to:

- completely remove a very small anal tumour

- remove a tumour that did not respond to chemoradiation

- treat anal cancer that comes back (recurs) after other treatments (called salvage surgery)

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

- repair an abnormal opening between the anus and the surrounding perianal skin (called a fistula) before starting chemoradiation

-

create an

ostomy if the cancer or treatment for the cancer causesincontinence

The following types of surgery are used when treating anal cancer.

Wide local excision

A wide local excision removes the tumour and a small amount of tissue around it (called the surgical margin). The surgeon may use special equipment, such as a small tube called an anoscope, to do a wide local excision. This surgery is also called a local resection.

Doctors use wide local excision to treat stage 0 or stage 1 anal cancer in the perianal area. It is often the only treatment needed for these early stages. This treatment does not harm or remove the muscles of the anal sphincter, so after the surgery you will be able to have bowel movements (poop) normally.

A wide local excision may also be used for more advanced anal cancer if the tumour causes symptoms such as pain and bleeding.

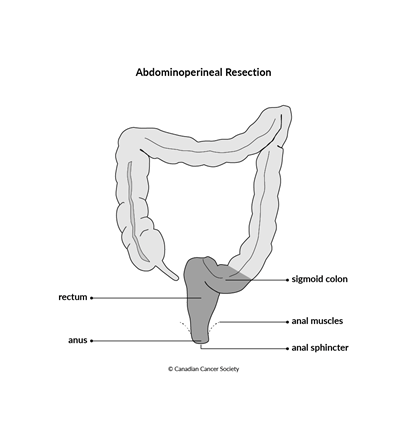

Abdominoperineal resection

An abdominoperineal resection is a type of bowel resection. During this surgery, the surgeon makes one incision, or cut, in the abdomen and another in the perineum (the area between the anus and vulva or between the anus and scrotum). The surgeon then removes the rectum, anal sphincter, anus and the muscles around the anus.

After this surgery, the waste from digestion (stool, or poop) will need a new path to leave your body because the anal sphincter has been removed. You need the anal sphincter in order to have a bowel movement (poop). You will have a permanent colostomy.

Research has shown that chemoradiation is an effective treatment for anal cancer, that helps preserve the function of the anus and quality of life. Because of this, an abdominoperineal resection isn't done as often as it used to be, as it permanently changes the way your body works. It is done if chemoradiation didn't destroy all the cancer cells or if cancer comes back after chemoradiation.

Find out more about bowel resection, including abdominoperineal resection, and about colostomy.

Inguinal lymph node dissection

An inguinal lymph node dissection removes lymph nodes from the groin. It may be done at the same time as an abdominoperineal resection to treat stage 3B anal cancer.

Find out more about inguinal lymph node dissection.

Fistula repair

Some people diagnosed with anal cancer have an abnormal opening or passage between the anus and the surrounding perianal skin. This is called an anal fistula, or a perianal fistula. The fistula's internal opening is in the anus and the external opening is typically on the skin around the anus or on the buttocks. A fistula can become infected or get bigger during chemoradiation treatment.

You will likely need surgery to repair a fistula. This is usually done after cancer treatment because having surgery and waiting for the area to heal will delay treating the anal cancer. In order to get started on cancer treatment, a surgeon can put a seton in place in the fistula. A seton, which can be made of different materials such as cloth or rubber, allows the fistula to drain and lessens the chances of the fistula causing problems during treatment. The seton is threaded from the external opening of the fistula through the fistula tract and out the anus, and tied in a loop so it stays in place.

The seton will stay in place during chemoradiation treatments and for up to 18 months after to allow the tissues to heal from radiation therapy. Once you have healed from treatment, surgery to fix the fistula can be done. This usually means cutting open the skin and muscle that is over the abnormal opening to convert it from a tunnel to an open groove. This allows the fistula tract to heal.

Side effects

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery, the effects of other treatments (such as radiation therapy) and your overall health. Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Side effects can develop any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

A wide local excision for anal cancer may cause these side effects:

- scarring

- bleeding

- infection

- numbness or tingling from nerve damage

An abdominoperineal resection for anal cancer may cause these side effects:

- diarrhea

- constipation

- fibrous tissue, or scars that make organs and tissues stick together (called abdominal adhesions)

- bowel obstruction

- sexual problems such as erectile dysfunction and ejaculation problems

- sexual problems such as vaginal pain and discomfort during sex

- urinary incontinence, including the need to pee (urinate) often and the intense need to pee

Find out more about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.